DNA mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) is a genetic condition often associated with colon cancer. It can happen in otherwise normal cells before cancer forms or after a tumor has already formed. The condition makes it hard for cells to correct mistakes that occur in DNA copying. This can lead to many mutations within tumors, or a high tumor mutation burden (TMB).

Some patients with high TMB respond well to immunotherapy, which uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer cells. But immunotherapy doesn’t work for more than half of patients with advanced MMRd tumors. Now, research from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Assistant Professor Peter Westcott may help explain why.

As a postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Westcott and his colleagues created new mouse models to study differing responses to immunotherapy in colon and lung cancers from MMRd. The models had more mutations across their genomes to more accurately reflect tumors seen in human patients.

For years, researchers thought that more mutations in cells lead to a better immune response in cancer patients because their bodies have an easier time recognizing tumors. Some doctors see high TMB as an indication that immunotherapy will work well. In fact, even the FDA says high TMB can qualify patients for some immunotherapy treatments. But when Westcott’s team tested their models for immune response, they found none. Westcott says:

“There’s no question these tumors are DNA MMRd, yet they’re not responding. That alone is a profoundly interesting negative result.”

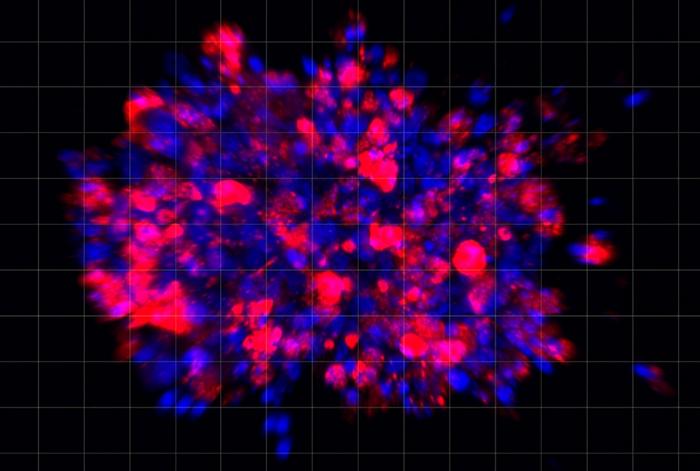

Westcott had a hypothesis. Although the tumors had many mutations, maybe they were too different from cell to cell to trigger an immune response. To test it out, the team isolated tumors with identical mutations in all cells, or clonal mutations, and tumors with identical mutations in only some cells, or subclonal tumors. They found that mice with clonal mutations responded to immunotherapy. Those with subclonal mutations did not.

The team also examined data from two small human clinical trials, and the hypothesis still held up. This remains the only human clinical trial data publicly available. Nevertheless, the potential clinical implications are staggering. Westcott says:

“If we can know if a patient’s going to respond to therapy or not, that’s extremely important information. Patients will have a much better sense of ‘Is immune therapy right for me, or do I have to look elsewhere for treatment?’”

With more research, this finding could offer a new way to determine if immunotherapy is a viable treatment option for patients with MMRd.

Journal

Nature Genetics

DOI

10.1038/s41588-023-01499-4

Article Title

Mismatch repair deficiency is not sufficient to elicit tumor immunogenicity