Government

The value of oncology drugs

As oncology drugs receive accelerated approvals, payers are questioning whether the benefits of these products outweigh the cost, spurring manufacturers…

The value of oncology drugs

As oncology drugs receive accelerated approvals, payers are questioning whether the benefits of these products outweigh the cost, spurring manufacturers to explore value-based agreements.

By Christiane Truelove • chris.truelove@medadnews.com

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s accelerated approval pathway for oncology drugs was intended to speed to market life-saving products and give patients earlier access. Confirmatory trials after approval (Phase IV trials) are supposed to demonstrate the benefits and effectiveness of the drug.

The problem: confirmatory trials for several indications for oncology drugs have failed to show clinical benefits. According to an article a year ago in The ASCO Post, “Oncology Drugs with Accelerated Approval: Is It Time for a Reset?”, sponsors have withdrawn cancer approvals for 15 clinical indications, and in 2021 alone, confirmatory Phase IV clinical trials failed to demonstrate clinical benefit for 10 drug indications that had received accelerated approval by the FDA. For example, in 2021 Merck & Co. withdrew the indication for its cancer drug Keytruda for metastatic small cell lung cancer with disease progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

2021 also marked AstraZeneca’s withdrawal of Imfinzi and Roche/Genentech’s withdrawal of Tecentriq for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment of

platinum-containing chemotherapy; and BMS’s withdrawal of Opdivo for hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib.

In 2022, FDA completed withdrawals of seven accelerated approvals for oncology drug indications. These include Keytruda for recurrent or locally advanced or metastatic gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma whose tumors express PD-L1 [CPS ≥1] as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression on/after two or more prior lines of therapy including fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-

containing chemotherapy and if appropriate, HER2/NEU targeted therapy; Tecentriq for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumors express PD-L1 as determined by an FDA-approved test or who are not eligible for any platinum-containing chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 status; and Acrotech Biopharma LLC’s Marqibo for adults with Philadelphia (PH) chromosome negative (-) ALL in second relapse or greater relapsed or whose disease has progressed following two or greater treatment lines of anti-leukemia therapies.

As a result of the greater scrutiny of accelerated approvals and in light of high prices for new therapies and high-profile withdrawals, payers and pharma companies are exploring the use of value-based contracting. Value-based contracts (VBCs), also known as value-based pharmaceutical contracts, are performance-based reimbursement agreements between healthcare payers and pharmaceutical manufacturers in which the price, amount, or nature of reimbursement is tied to

value-based outcomes.

“They’re a very interesting topic to everybody in the industry; it’s kind of one of the sexy topics that everybody’s pursuing,” says Ed Schoonveld, managing principal, Value & Access, ZS Associates.

Andrew Hertler, M.D., chief medical officer at New Century Health, which works with payers to do utilization quality management for specialty care delivery in cardiology and oncology, says interest in VBCs for oncology drugs is strong among some payers because “we’ve reached a point where about 60 percent of the spend is driven by the drugs itself.”

Historically, payers have managed these costs through managing utilization, looking very closely at factors such as the efficacy of a drug, how much benefit it offered to patients, the toxicity of the drug, as well as the cost, and trying to help guide physicians to the highest-base, value-based choices.

“And that has been successful to a point,” Dr. Hertler says. “But as we thought about it, we are really trying to control a unit/cost problem with a utilization solution, which is why we’re very much interested in utilization and value-based contracting.”

While they have no control in how the FDA approves drugs, Dr. Hertler’s company works with payers who are “frustrated” with the state of the accelerated approval program, he told Med Ad News. “[Payers] are frustrated with drugs that are incredibly expensive, yet have not shown proven benefits in terms of outcome.”

In October 2021, Takeda Pharmaceuticals became one of the first companies to launch a value-based agreement for an oncology drug, signing an innovative risk-sharing agreement with New England-based Point32Health around Alunbrig, a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that is approved for adult patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The contract, which executives say is among the first risk-sharing contracts in oncology and the very first in ALK+NSCLC, makes Alunbrig broadly available to Point32Health’s more than 2 million members, and Takeda is standing behind the medicine with a unique outcomes-based structure.

Under the agreement, if an ALK-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patient on Alunbrig discontinues treatment within 100 days of starting therapy, the drugmaker will pay the insurer a rebate. If patients had to pay out of pocket for the drug, they would be entitled to a share of the rebate if they discontinued within that 100-day window.

Although there have been a few value-based contracts in the United States for drugs, most of these types of agreements have been done in Europe. Manufacturers have made VBCs for rare disease and oncology with health authorities in Italy, the United Kingdom, Australia, and other countries, Schoonveld notes.

Facing the challenges

Takeda’s deal has not unleashed a flood of similar agreements. Although there has been a lot of discussion about value-based contracts for oncology drugs, experts at Deloitte say despite a growing interest in VBCs, adoption has been slower for numerous reasons including misaligned incentives, difficulty tracking patient outcomes, and lack of consensus on industry standards.

“There’s no doubt that value-based contracting is challenging in oncology,” says Casey McCann, executive director, Value, Access & Reimbursement Strategy, Klick Health. “Administrative burden on payers and difficult-to-measure results call for a significant level of cooperation and risk-sharing between payers and manufacturers. Currently, the most straightforward VBCs include metrics that are reasonably easy to quantify, such as adherence and hospitalizations.

“The goal for VBCs in the future is to determine how to adequately and objectively measure clinical outcomes associated with specific oncology treatments. In addition to aligning on metrics at the contact level, oncologists must be considered key VBC stakeholders as they can drive care coordination and clinical outcomes. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of MN implemented a value-based contract that focused on preventing unnecessary hospital visits through care coordination, which reduced cancer care costs by more than 10 percent for patients in that plan.”

According to Jennifer Hinkel, director, the Data Economics company, policy mechanisms such as the Inflation Reduction Act – which will allow Medicare to negotiate prices for some drugs starting in 2026 – are going to drive the move towards what she calls “true value-based agreements or true outcomes-based agreements.”

The price tags of gene-based or CAR T one-and-done, expensive therapies will also play a role, Hinkel believes, because “our [healthcare] system is just not set up to have these big upfront payments.”

According to Raymond Johnson, senior VP of market access strategy at Ogilvy Health, while a decade ago the industry and payers were able to create VBCs for diabetes and heart disease therapies, oncology poses some barriers.

“When we were looking at diabetes, and we’re looking at hypertension, they’re sort of hard-and-fast clinical outcomes, primary endpoints like A1C and so forth, that are measurable, and usually are measurable within a certain time frame,” Johnson told Med Ad News. “And it’s more or less a linear sort of agreement.”

In cancer, however, “one of the challenges is that there aren’t necessarily the hard-and-fast endpoints that, thinking about a tumor progression and metastases, it’s not linear, it’s very unique to each patient and patient reactions across different therapies,” Johnson says.

Another challenge with trying to get VBCs in oncology is the way that cancer care is delivered in the United States, says Christina Corridon, principal at ZS Associates and the global leader of the consultancy’s oncology vertical.

Corridon notes that in the United States, although there is a lot of heterogeneity in the way healthcare is delivered, in oncology, there is another divide between community-based cancer care and academic care – the latter being where most of the clinical trials are taking place, and where patients are getting drugs before they are initially approved or even have new indications. Additionally, more than 50 percent of the oncology blockbusters are products that have more than a billion dollars in revenue.

“Those which have significant budget impact are indicated in more than three distinct tumors,” Corridon says. “Some of them have upwards of seven indications or they’re indicated in seven different diseases. And so there’s a ton of complexity in what a [value-based] contract looks like in that situation, because of how you can report back which indication that it’s used in an update. And most of those larger blockbusters are also again, the areas where there’s a lot of spend, and where there’s been a lot of growth in the last five years – breast cancer, NSCLC, prostate, multiple myeloma, which, in 2021, represented more than 55 percent of total worldwide sales.”

Although there is a lot of new drug development and competitiveness in these indications, which is good for patients, many of these drugs are also targeted to a very specific patient population that is smaller than the overall population for that indication.

For companies looking to negotiate VBCs with payers, such contracts may be for the launch of later indications, rather than the initial launch of the drug, Corridon says.

All of these factors make it more difficult and unwieldy to pull off a value-based contract for oncology drugs. “It’s crowded, it’s complex, [and] it’s only becoming increasingly so,” Corridon told Med Ad News.

Schoonveld notes while payers may like the idea of VBCs, “they have some concerns”. They find that generally, the definition of value is not necessarily the same between them and the pharma company or the provider.

Payers also have trust issues with pharma about the intents of such agreements, he adds.

According to McCann, “We believe existing VBCs for oncology drugs will continue to be focused on persistence or resource utilization due to the ease of measurement. VBCs for oncology that can provide clearly measurable outcomes – clinical or economic – will be more likely to meet the goals of both payers and manufacturers. Manufacturers can even plan ahead for the possibility of VBCs as early as the clinical trial stage to establish viable endpoints (or surrogate endpoints) that can be easily measured by payers.”

From the beginning of talking with payers about any drug, pharma manufacturers need to show that they have the evidence, Dr. Hertler says. However, because of the way accelerated approvals work in oncology, the kind of evidence payers are looking for just isn’t there.

“We look very carefully at the clinical evidence in the clinical trial they’ve done and what we’re really interested in is comparative effectiveness,” he says. “We’ve got many options for almost any patient with cancer, but [we’re looking at] which has the greatest efficacy, the least toxicity. And what you love to see is a well done, randomized clinical trial comparing a new therapy to the existing standard of care. And, unfortunately, we very often do not see that.”

Manufacturers and payers are working at cross-purposes. “We, as clinicians, are looking for comparative effectiveness,” Dr. Hertler says. “If I’m a pharma manufacturer in the way we built the system, I’m looking at my drug getting approved.”

But even in those confirmatory trials for an accelerated approval, manufacturers are not coming up with the data needed.

“We see randomized trials where what they’re comparing it to is what I would characterize as a straw man,” Dr. Hertler says. “And by that I mean a therapy that, quite frankly, we as oncologists have not used for 10 years. And, meanwhile, the other standard that the other drugs were using, were also compared to a straw man made many times the same, but sometimes different, and then slightly different patient populations. So we’re left comparing apples to oranges, in terms of which one we utilize.

“Run your trial against the standard care, make it a randomized Phase III trial, and show us overall survival data, or at least very, very strong progression-free survival data. That’s the kind of drugs that we want to encourage people to utilize. But when you present a drug, with response rate data alone, it’s not compared to the standard of care. And it’s small numbers. Until that gap is developed, if there are alternatives, we’re going to push the alternatives and actively discourage those drugs.”

One of the goals of the manufacturer should be to partner with the payers as well as centers of excellence and health plans, Johnson says.

In creating a VBC, especially for drugs that are expected to be approved for more indications, manufacturers can run a pilot program to test the foundations before the program officially launches, Johnson says. “Think about that plan over the first 12 to 18 months of commercialization. Get in where you fit, show improvement, and then you’ll be able to roll that out to a broader customer base.”

As far as being able to capture the value of the product in a VBC, it’s more than just the cost of the drug weighed against the outcomes. “It’s not just the pharmacy benefit,” Johnson says. “It’s also ED visits, hospital admissions, it may be off-scheduled doctor visits, testing and labs and things of that nature. It translates into a really big tree to kind of get your arms around.”

McCann says while payers tend to be cautious about taking on the risk of a VBC, they seem to be most comfortable with an agreement where success is measured in terms of resource utilization.

“In a world of progression-free survival, overall survival, and other more subjective oncology endpoints, the burden and risk for payers can make it difficult to confidently engage in VBCs,” McCann told Med Ad News. “The key to success lies in maintaining trust and transparency between the payer and the manufacturer by mutually defining what data to collect, when to collect it, and how to translate it to the terms of the contract. As technology continues to advance, VBCs will become easier to implement and will hopefully result in better outcomes while stabilizing cost predictability.”

The role of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in VBCs should not be overlooked, McCann says. “In fact, PBMs can play an important role in not only collecting pharmacy data, but in directly driving outcomes and supporting predictable costs for health plans,” he says. “In some cases, a third-party organization can lead the contract negotiations to ensure an equitable exchange for all parties. “

Leveraging third-party organizations that specialize in VBCs can be a particularly good way to help persuade payers to consider a VBC, McCann says. “The inclusion of a third-party partner helps to ensure that the contract is fair, equitable, and transparent, especially if there is a health plan and a separate PBM involved. It’s also important to consider the issues surrounding health equity – the social determinants of health – to support patient adherence and ensure the success of VBCs that are in place. Patient support programs are well situated to address this issue and support mutually desirable outcomes.”

And when it comes to creating VBCs for oncologic cell and gene therapies, pharma manufacturers will need new ways to measure value.

“In some cases, manufacturers can work with payers to establish payments over time for costly, curative intent treatments,” McCann says. “This is also where PBMs can play a role in VBCs associated with high-cost curative therapies – making costs more predictable by allowing payer stakeholders to spread the payments out over time.”

For example, Express Scripts (ESI) and Cigna launched a program called Embarc that offered employers and health plans a predictable cost for gene therapies by providing a long-term payment agreement – less than $1 per member, per month (PMPM).

“In some cases, health plans may require longitudinal assessments of efficacy (using direct or surrogate endpoints) to help justify the continued cost of therapy and ensure oncology patients receive the treatment they need,” McCann says. “The role of PBMs in VBCs is likely to grow in the future, as they are uniquely positioned to collect and monitor data, as well as impact patient outcomes.”

Johnson says the lack of VBCs in general, not just for oncology drugs, is a sign of just how difficult it is at present to come to an agreement on value determinations. “I was speaking with a colleague and we realized that maybe somewhere around 50 percent, maybe a little south, [of VBCs] actually are realized, in terms of delivering on the promise of the VBC, and it’s not for lack of trying. It’s just the total support, the total infrastructure is just not yet in place.”

|

Chris Truelove is contributing editor of Med Ad News and PharmaLive.com. |

Here Are the Champions! Our Top Performing Stories in 2023

It has been quite a year – not just for the psychedelic industry, but also for humanity as a whole. Volatile might not be the most elegant word for it,…

AI can already diagnose depression better than a doctor and tell you which treatment is best

Artificial intelligence (AI) shows great promise in revolutionizing the diagnosis and treatment of depression, offering more accurate diagnoses and predicting…

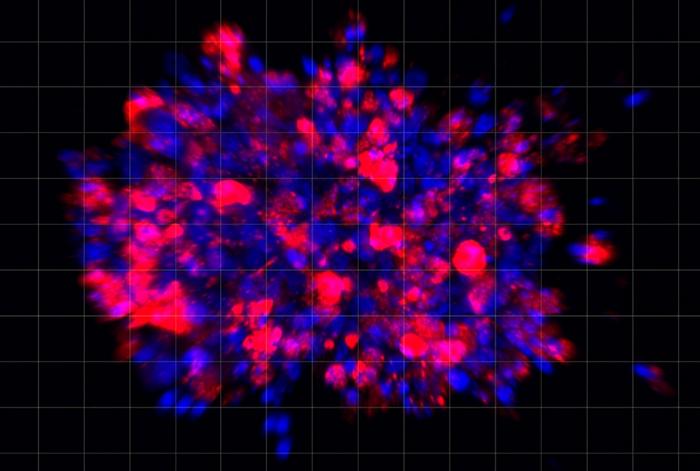

Scientists use organoid model to identify potential new pancreatic cancer treatment

A drug screening system that models cancers using lab-grown tissues called organoids has helped uncover a promising target for future pancreatic cancer…