Medtech

Q&A: Model Act to Limit Out-of-Network Provider Rates

The post Q&A: Model Act to Limit Out-of-Network Provider Rates appeared first on The National Academy for State Health Policy.

Q&A: Model Act to Limit Out-of-Network Provider Rates

November 9, 2022 / by Johanna Butler, Erin Fuse Brown, and Maureen Hensley-Quinn

What problem is this policy addressing?

Affordability: This model aims to address high and rising prices that increasingly result in unaffordable health care for purchasers, particularly employers and consumers. Nearly 1 in 10 adults have outstanding medical debt. Health insurance premiums are rising again and increasingly employers report they cannot continue to increase cost-sharing for their employees. Many households do not have enough savings to pay typical health plan deductibles, and cannot afford to use health services to meet high deductibles. In short, consumers across the country face an affordability crisis.

Health Plans’ Weakened Negotiating Authority: Facing high premiums and hospital costs, policymakers, employers, and consumers might ask why health plans aren’t doing a better job negotiating for lower prices with hospitals. There are several factors that may force a health plan to accept demands for high prices or exorbitant price increases.

- To meet network adequacy standards, health plans have limited bargaining power when negotiating prices with “must have” providers or large health systems. Health plans may agree to pay high-priced providers to meet federal and/or state provider network adequacy requirements.

- Hospitals and health systems may threaten to charge high out-of-network prices. In response, plans may opt to keep a hospital in-network and accept a demanded price increase because the cost of the alternative – even a small number of patients going out-of-network – is more expensive for the plan.

- There are also client considerations that may sway a health plan – employers or employees often prefer broader networks so plans may want to keep a hospital in-network to remain competitive. Employers report that to recruit and retain employees, which is critical to their success, their health plan needs to include certain physicians and/or hospitals in network.

In-Network Participation: There are several recent examples of large hospital systems across the country threatening or leaving the network of a local health plan over reimbursement negotiations. In Texas, one of the region’s largest health systems teamed up with a prestigious provider network to demand an increase of over $900 million in reimbursements from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas, the state’s largest insurer. When BCBS did not immediately agree, providers filed to terminate their contracts and go out-of-network. This would mean over 450,000 patients would face high out-of-network prices and be forced to find new providers or drop their plan for a different one. These dynamics are playing out across the country.

How does this model address affordability and access problems?

By reducing the value of the hospital threat of staying out-of-network, an out-of-network rate limit can reduce in-network negotiated rates, encourage providers to remain in-network, and reduce overall spending. Out-of-network payment limits can level the bargaining dynamic between carriers and powerful providers, which could result in lower costs and increased access for patients.

Prohibitions on surprise billing to date have largely focused on protecting consumers from high costs when seeing an out-of-network provider. Researchers have argued that the indirect impact of limiting all out-of-network payments to hospitals, through influence on in-network negotiated rates, could be far more impactful for overall health care affordability.

Why does the model set the limit at either a percentage of Medicare or the median in-network rate?

While it would be administratively simpler to go with a percentage of Medicare only, most of the out-of-network payment standards in state and federal surprise billing laws base concepts of an “appropriate out-of-network rate” on median in-network rates. The median, and not the mean, should be used because the mean could be skewed upward by the presence of a dominant provider. Additionally, in many cases, and depending on which multiple of Medicare a state chooses, the X% of Medicare could be higher than the median in-network rate. There could also be cases where Medicare rates are based on a very small number of claims so are not as helpful (e.g., maternity or pediatric services). The “lesser of the two” approach corrects for both potential issues and ensures that some services will not go up in cost compared to the current median rates.

However, ultimately using just Medicare or the “lesser of two” approach is a state’s policy choice. A state could likely move forward with a cap based solely on Medicare to simplify but policymakers should be aware of possible unintended consequences or complications. Some experts have also suggested that Tri-Care diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment rates could serve as an alternative to Medicare for cases like maternity, newborn, or pediatric services if a state chooses to go with a Medicare-only approach.

How should states determine the right Medicare percentage?

The value of the multiple of Medicare rates would depend on the state’s hospital costs, which could be quantified using NASHP’s hospital cost tool. NASHP’s interactive Hospital Cost Tool provides anyone from policymakers to researchers with insights into how much hospitals spend on patient care services. The tool also shows how those costs relate to both the hospital charges (list prices) and the actual prices paid by health plans. If available, a state could also use its All-Payer Claims Database (APCD) to help inform a decision on setting a Medicare benchmark.

Researchers at RAND modeled the potential impact of a national out-of-network payment limit and looked at how it would change average out-of-network payments and nationwide hospital spending. They found overall savings if the cap was set at 125% of Medicare, more moderately at 200% of Medicare, or at the state’s current average payments by private plans.

In 2017, Oregon enacted legislation to cap both in- and out-of-network prices for most hospitals participating in its public employee health plan, with in-network rates capped at 200% of Medicare rates and out-of-network rates capped at 185% of Medicare. A March 2022 audit found that the state plan saw savings of $59 million in 2020 – this translates to about 14% of facility claims subject to the law.

How is this different than surprise or balance billing laws? Does this conflict with the federal No Surprise Act (NSA)?

Federal and state surprise billing laws and an out-of-network payment cap are complementary but distinct policies. An out-of-network payment limit is intended to shift the negotiating dynamic and create incentives for hospitals to remain in-network at lower rates. This differs from surprise billing laws which generally aim to protect consumers and ensure they aren’t left with unplanned, high medical bills.

The NASHP out-of-network payment limit model applies to a broader range of services, including all out-of-network services, not just those in an emergency or at an in-network facility. It also targets hospital payments not physician payments, unlike most surprise billing laws.

However, on services where an out-of-network limit and surprise billing protections could overlap, such as for hospital emergency department charges, the out-of-network payment limit could potentially substitute the federal No Surprises Act (NSA)’s out-of-network payment calculation methods used in dispute resolution. This is because the NSA defers to state methodologies for determining out-of-network payment amounts, particularly for non-self-funded ERISA plans. Although the NSA rules are being challenged in lawsuits, HHS’s current approach places significant weight on the median in-network rate as the starting point for determining an appropriate out-of-network “qualifying payment amount.” Thus, the models’ reference to the median in-network rate allows states to build on ongoing work to implement the NSA and use a benchmark that will be more broadly used.

How will this be enforced?

To enforce providers’ compliance with the out-of-network rate limit, the model proposes (a) making a violation an unfair trade practice enforceable by the relevant agency, state Attorney General, and affected individual; (b) requiring the provider to refund the health plan and pay a penalty payment to the affected individual; and (c) providing authority for the enforcing state agency to audit providers and payers to support enforcement.

How can we ensure savings will be passed on to consumers?

States must actively oversee health plans to ensure that possible savings are passed on to consumers in the form of lower cost-sharing and/or premiums. To evaluate whether health insurers are passing on savings generated by the out-of-network rate limit, state departments of insurance can use authority under the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) requirements and insurance rate review.

- Premium Rate Review: Insurers are subject to certain requirements under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to have their plans and premium rates reviewed annually. While rate review was ongoing on the state-level before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted, the ACA created a floor for review of “unreasonable” increases or a 10 percent increase in the individual or small-group market.

- MLR Requirements: The ACA also added the medical loss ratio (MLR) requirement, which limits the amount of premium dollars that insurers can spend on administration, marketing, and profits. The ACA requires most individual and small-group market insurers to spend 80 percent of premium income on health care claims and limits other expenses to the remaining 20 percent of premium income.

It may take some time after implementation to determine how much savings are generated, and whether additional policies such as a premium growth cap are needed. NASHP’s model provides additional rulemaking authority for a Commissioner of Insurance to promulgate regulations necessary to evaluate growth or reduction of premiums to ensure savings are appropriately passed on to consumers.

Could an out-of-network limit negatively impact consumer access?

The goal of the policy is to set an out-of-network cap to drive in-network participation and increase access to and the affordability of care. However, if providers opt not to participate in a health plan’s network and their out-of-network rates are capped, could providers refuse to provide services for out-of-network consumers in non-emergency settings? It is unknown if this policy would increase the likelihood of providers refusing service to out-of-network patients more than is already occurring without it. Since out-of-network costs can be significantly higher than in-network costs and consumer cost-sharing is typically higher for out of network care, capping the prices could increase the likelihood that patients could afford such services, mitigating access concerns.

Federal requirements under the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) will ensure patients are still seen for emergency care regardless of network participation. Additionally, network adequacy laws will offer some protections. Network adequacy requirements can be an important backstop to ensure appropriate consumer access if state insurance commissioners have adequate authority and resources to enforce the requirements. States may also consider strengthening or updating network adequacy requirements to protect consumers most effectively. Health plans and state officials should actively monitor for this unintended consequence.

Should a state be concerned about preemption by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) if it applies the out-of-network rate limit to self-funded employer-based plans?

The model’s key policy requirement, limiting out-of-network rates for inpatient and outpatient hospital services, should not be preempted by ERISA. The out-of-network rate limit is a form of provider rate regulation, and there’s strong precedent under the New York State Conference of Blue Cross Blue Shield Plans v. Travelers Ins. Co. (1995) and Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (2020) cases that state laws that engage in provider rate regulation or health care cost regulation are not preempted by ERISA. In addition, there’s more room to require participation by third-party administrators (TPAs) of self-funded plans after Rutledge, which noted that a state law regulating a PBM that contracted with an ERISA plan was not regulating the ERISA plan itself.

Although states have broader authority to require TPAs of self-funded plans to participate in health care cost regulations, state reporting requirements are preempted by ERISA under the Gobeille v. Liberty Mutual case (2016). Thus, the model law’s health carrier data reporting requirement is limited to state-regulated fully insured plans and the TPA for the state or public employee health plan (which are exempted from ERISA as a government plans). Nonetheless, the self-funded ERISA plans and their TPAs could still contribute data voluntarily, which they may be willing to do if the model law’s effect is to save the plan money and encourage in-network participation by dominant health systems.

Equity Impact Review

Reflecting state efforts to better analyze the impact of proposed policies on health equity, NASHP adapted the following questions used by legislative committees in Maine to review the model legislation.

Is the problem the legislation is addressing one that is worse or exacerbated for historically disadvantaged racial populations?

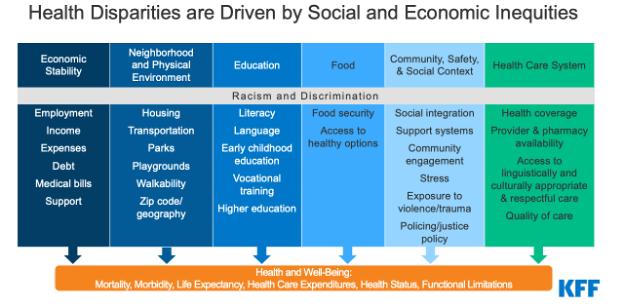

Health care affordability challenges heighten existing health disparities and exacerbate health inequities across communities, disproportionately impacting people of color, those with disabilities or chronic health conditions, low-income Americans, and those in underserved rural and urban areas. Historically disadvantaged communities are disproportionately impacted by chronic illnesses and certain health conditions, such as diabetes, HIV/AIDs, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and asthma. These conditions require affordable, regular access to health care services, which are threatened by high prices.

There is also a negative feedback loop between health and wealth racial disparities. The racial health gap refers to disparities in health care access, quality, and outcomes across racial groups while the racial wealth gap refers to disparities in income, assets, and debts across households. Patients may get trapped in a cycle wherein costly care to treat chronic conditions impedes wealth development and results in an accumulation of medical debt. Stress from financial strain and medical debt can then lead to avoiding care and worse health outcomes.

Additionally, Black patients are more likely to report unmet behavioral health needs; however patients are more likely to receive services such as substance use disorder treatment and mental health services from out-of-network providers. As such, these services are made even less accessible, exacerbating health disparities. Maintaining a continuous patient relationship with behavioral health providers may be particularly important, so driving greater in-network participation could increase access for patients with unmet behavioral health needs.

What factors contribute to or compound racial inequities around this problem?

Income inequality, insurance status, geographic location, and the health-wealth feedback loop compound racial inequities around access to affordable health care. Low-income households and uninsured individuals are more likely to experience affordability challenges.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Have we engaged diverse stakeholders?

The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) is a nonpartisan organization and engages diverse states and various government offices including legislatures, Governor’s offices, state employee health plans, etc. This model has been reviewed by a number of state officials. In addition, NASHP received feedback and input from a variety of academic experts and partner groups that represent the spectrum of health care purchasers – patients, families, unions, and employers. NASHP actively seeks out different perspectives to gauge possible unintended consequences of model legislation.

Broadly speaking, is this approach neutral to historical/ongoing racial inequities, or does it further them or counter them?

Broadly, this model is neutral to historical/ongoing racial inequities in health care affordability. Capping out-of-network provider payments will change the negotiating dynamic between insurers and hospitals to potentially increase network participation, lower in-network prices, and improve affordability and access to care. While this model does not specifically target or correct ongoing health inequities, it does tackle high health care prices, which disproportionately impact historically disadvantaged communities.

This Q&A document and the accompanying model legislation were produced with support from Arnold Ventures.

Related Information

The post Q&A: Model Act to Limit Out-of-Network Provider Rates appeared first on The National Academy for State Health Policy.

ETF Talk: AI is ‘Big Generator’

Second nature comes alive Even if you close your eyes We exist through this strange device — Yes, “Big Generator” Artificial intelligence (AI) has…

Apple gets an appeals court win for its Apple Watch

Apple has at least a couple more weeks before it has to worry about another sales ban.

Federal court blocks ban on Apple Watches after Apple appeal

A federal appeals court has temporarily blocked a sweeping import ban on Apple’s latest smartwatches while the patent dispute winds its way through…