Psychedelics

Psychedelics Could Change Human Evolution – if Science Allows It

The reality of what psilocybin is and what it does within the human body is difficult to pinpoint.

The post Psychedelics Could Change Human Evolution –…

Psilocybin can change the world. At least that’s what Paul Stamets, mycologist, scientist, and one of the key thought-leaders of today’s modern psychedelics industry, believes.

In a presentation during the Wonderland Psychedelics conference in Miami in November, Stamets said that psilocybin reduces violence and breaks addictive behavior.

“We know psilocybin is very helpful for PTSD and depression. So this is a game changer, fundamentally, across our society,” he said. “So for any law enforcement out there, your jobs will be easier. You’ll have better encounters with the citizens. You won’t be demonizing the citizens. You will have empathy and understanding that people are all trying to work together. This is truly a medicine for the masses.

“We’re not the homo sapiens of the past 2,000 years. It is time for us to evolve into a new species. I believe that this can help us neurologically to become a new species. I think our time is more at the threshold of a revolution from the underground. We all can participate in this.”

But while Stamets hopes to create a utopia built on the mostly anecdotal evidence of the effectiveness of psilocybin, a substance used by humans for thousands of years, the reality of what psilocybin is and what it does within the human body is a bit more difficult to pinpoint. Sandoz chemist Albert Hofmann isolated and determined the structure of psilocybin in the early 1960s, but there is still some question about how the actual hallucinogenic chemical inside the mushroom is created.

Science has to have its say – to clearly measure the effectiveness and safety of this or any psychedelic compound – if a company wants to bank on psilocybin as their money-making wonder drug. And science is still looking for clear measurements.

For example, scientific literature suggests psilocybin has low toxicity, low risk of addiction, overdose, or other causes of injury commonly caused by substances of abuse. “However, the presence of negative outcomes linked to psilocybin use is not clear yet,” a study reported, adding that “there is no scientific consensus on the risks that the use of psilocybin may bring.”

Researchers analyzed 346 reports of psilocybin use and found that bad trips were more frequent in female users, primarily associated with thinking distortions. The use of multiple doses of psilocybin in the same session or in combination with other substances was linked to the occurrence of long-term negative outcomes.

In another recent study, 10.7% of users reported that, under psilocybin, they placed themselves or others at risk of physical damage; 2.6% reported being violent or physically aggressive with themselves or others; and 2.7% sought help in a hospital or emergency room.

Researchers pointed out that these self-reporting results used in that study came from black market purchases of psilocybin, which opens up the possibility that users weren’t getting the correct dosage or even the correct “magic mushroom” (there are reportedly 180 species of psilocybin-containing mushroom) with the right level of the active hallucinogenic ingredient psilocin.

Most psilocybin users experience a pleasant alteration in mood, but some panic or become moody, according to a book about traditional medicines. Other adverse reactions to psilocybin include hypertension, exacerbation of preexisting psychosis, and hallucinogen-persisting perceptual disorder.

There are other issues in how the clinical trials are conducted. Treatment effect sizes in psychedelic random clinical trials are likely overestimated due to de-blinding of participants and high levels of response expectancy, according to one study.

Using a placebo to hide the effects that one group gets, as researchers have to do to study the differences between a real psychedelic and the placebo, is difficult. A test subject knows then they are experiencing the profound body-and-brain-tripping effect common with psilocybin.

Surveys can be problematic as well. For example, the National Household Survey (NHS) noticed an unusual increase in reported lifetime use of “any illicit drug” among its surveyed population, according to a report in Erowid, a nonprofit educational organization that provides information about psychoactive plants and chemicals, merely because of who was interviewing them.

Specifically, 39.9% of subjects interviewed by inexperienced interviewers (those with no previous NHS experience and with fewer than 20 interviews) reported ever having used an illicit drug. In comparison, the most experienced interviewers – those who had at least one prior year of NHS experience and conducted more than 100 surveys – received this response from only 30.6% of subjects. This means that an additional 9.3% of respondents admitted to illicit drug use when surveyed by an inexperienced interviewer.

The combination of the illegality of the activity, the explicit governmental and political desire to change people’s behavior, and the controversial nature of the subject make it impossible to trust most of what is reported as “factual” drug use statistics, according to the Erowid report.

Perhaps the largest overall problem with psychoactive-related surveys is not a problem with the data itself, but with how the results are (mis)used and (mis)understood, according to Erowid. The datasets generally say very little by themselves and require interpretation to be meaningful to most people. This process of interpretation and reporting may result in more distortion than the rest of the data problems combined.

Overstating reliability, taking numbers out of context, ignoring conflicting results, suggesting causality where there is only correlation, and other simple techniques can be (and are) used to make the data support just about any rhetorical or political point.

Today there is a certain balance in understanding psilocybin, as the psychedelics renaissance moves forward and more and more voices lend support to various beliefs sometimes at odds with each other. Better clinical trials, better surveys, and better understanding of the plant’s chemistry are all to come.

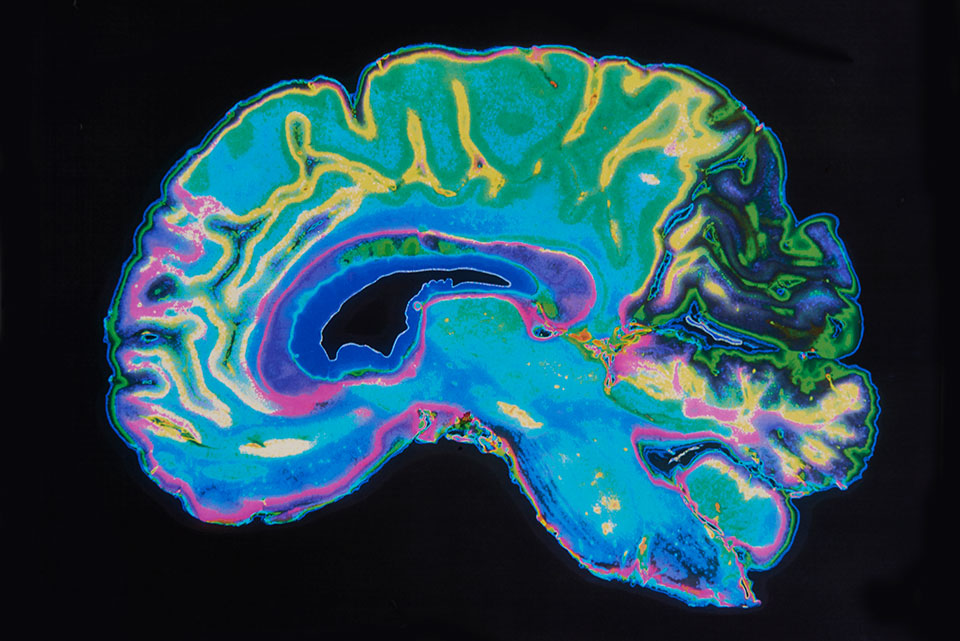

In fact, a new brain-mapping study is underway at the Washington University School of Medicine that hopes to answer some of the unknowns about how psilocybin acts in the human brain by establishing a neuroimaging paradigm for use in future clinical research testing the effectiveness of psilocybin in various clinical applications.

But for now, we are here:

- Psilocybin is a sacred plant used by humans for thousands of years that may profoundly change how humans live and interact with each other. There is nothing inherently bad about them.

- Psilocybin is still a mystery, how it works from one person to the next is still questionable, and science needs to better understand it so that people hoping to benefit from it get the safe and effective help they need.

The post Psychedelics Could Change Human Evolution – if Science Allows It appeared first on Green Market Report.

psilocybin

psychedelic

psychoactive

depression

ptsd

hallucinogenic

Psychedelic Search Trends in 2023

Take a look at this 2023 search volume chart. Do you think you can guess what’s happening? I was pretty shocked when I noticed this spike for December…

Here Are the Champions! Our Top Performing Stories in 2023

It has been quite a year – not just for the psychedelic industry, but also for humanity as a whole. Volatile might not be the most elegant word for it,…

Psilocybin shows promise for treating eating disorders, but more controlled research is needed

Recent psychedelic research shows promising results for mental illnesses and eating disorders, with surveys and reports indicating psilocybin-assisted…